An examination of the People’s Republic of China draft Personal Information Protection Law published for consultation on 30 April 2021 reveals that its regulation of cross-border data transfer will have important consequences for individuals, businesses and judicial assistance.

To better protect personal information and develop the digital economy, China is taking action to enact its Personal Information Protection Law. On 30 April 2021, the second deliberation draft of the Personal Information Protection Law (hereinafter ‘Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law’) was published by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for public opinion (official version and unofficial English translation available). Regulating cross-border information flow is a highlight of the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law. Five important issues deserve attention.

- Critical information infrastructure operators and personal information handlers

The Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law broadly defines ‘personal information’ as any type of information recorded electronically or by other means that identifies or can identify natural persons, but does not include anonymised information (Article 4 of the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law).Unlike the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (hereinafter ‘GDPR’) which divides organisations and individuals that process personal information into data controllers and data processors, the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law does not make such distinction. It uses ‘personal information handlers’ to refer organisations or individuals that independently make decisions on personal information processing matters such as the purpose and methods of processing personal information (Article 72.1). Processing is widely defined as including the collection, storage, use, handling, transmission, provision and disclosure of personal information (Article 40).

The Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law requires that critical information infrastructure operators and personal information handlers that process personal information at the volume shall store the personal information which they collect or generated in China (Article 40) according to regulations of the Cyberspace Administration of China (Office of Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission) (hereinafter ‘CAC’). If this information should be transferred overseas, the relevant information handlers must pass a safety assessment organised by the CAC unless an exemption is available under relevant law, such as the standard contract (discussed below in section 3), and granted by the CAC (Articles 38(1) and 40). This provision is consistent with the Chinese Cybersecurity Law, which entered into force 6 January 2017. Its Article 37 provides that personal information and important data collected and produced by critical information infrastructure operators during their operations within the territory of China shall be stored within China. This is a comprehensive data localisation requirement. First, ‘critical information infrastructure’ has been defined broadly including but not limited to (1) infrastructure in important industries and fields such as public communications and information services, energy, transport, water conservancy, finance, public services and e-government affairs, and (2) other infrastructure which, in case of damage, lost functions or data leakage, will result in serious damage to state security, the national economy, people’s livelihood and public interest (Chinese Cybersecurity Law Article 31). This definition is expansive as energy, transport, water conservancy, finance, public services cover very large industries. Personal information, whether important or not, collected and produced by critical information infrastructure operators shall be stored within China. Second, this Article sets a default rule for data localisation and only in exceptional scenarios can critical information infrastructure operators provide such information and data to overseas parties or store it overseas. Critical information infrastructure operators shall conduct a security assessment according to the measures issued by the CAC in conjunction with relevant departments of the State Council (Chinese Cybersecurity Law Article 3). At present, the Chinese data regulatory system is constituted by a wide range of government agencies such as CAC, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, police and public security organs, the State Post Bureau, and the People’s Bank of China. Promoting consist data cross-border transfer assessment among regulatory agencies is necessary. The contents of this assessment have not been finalised, where the CAC has published draft papers ‘Measures to Assess Whether Personal information and Important Data Can be Moved outside of China’ for public consultation in April 2017 and June 2019.

- Transfer personal information overseas for a business reason

Where personal information handlers need to provide personal information overseas due to a business requirement, they shall obtain a personal information protection certification from a professional body in accordance with regulations of the CAC (Article 38(2)). It is unclear who is the professional body. The purpose of the certification is likely to ascertain that the protection of the personal information provided in the foreign state that receives the information should be equivalent to that of China. To achieve this goal, the CAC may authorise this professional body to issue decisions, like the EU ‘Adequacy Decision’ under the GDPR, to foreign jurisdictions that may receive cross-border information transferred from China. Protecting personal information is not considered an aspect of protecting fundamental human rights in China, and China may combine its adequacy decision, if any, with its free trade agreement or bilateral investment agreement negotiations. Alternatively, the professional body may issue certificates to certain entities that are considered as being capable to fulfil the requirement of protecting personal information under Chinese law.

- Standard contracts for cross-border personal information transfer

If a Chinese personal information handler decides to transfer personal information overseas, the contract concluded with the foreign recipient parties shall follow the standard contract designed by the CAC (Article 38.3). The standard contract has not been released but will specify the rights and obligations of the Chinese data handler and the overseas data recipient, and ensure personal information handling activities complying with the personal information protection standards under the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law. The EU also uses standard contracts to regulate cross border personal information transfer outlined in the EU Commission Decision of 5 February 2010 under Directive 95/46/C.

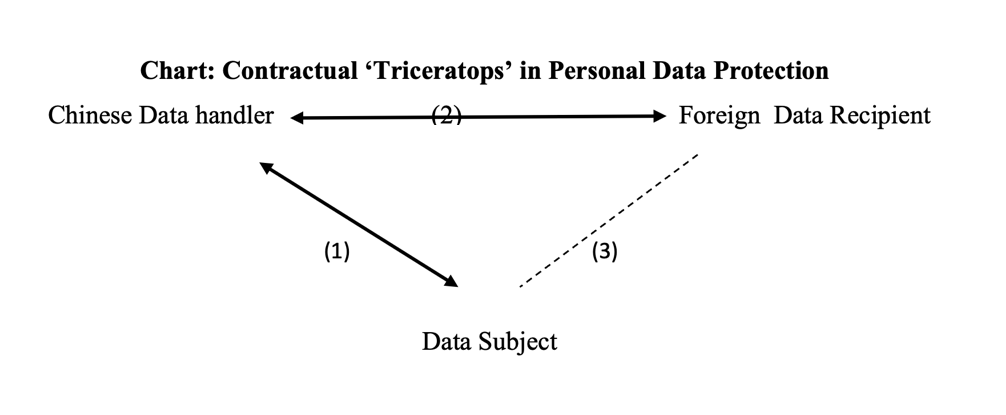

Notably, personal information protection involves a tri-party relationship: the contract between a data subject and a Chinese data handler (i.e. the solid line (1) in the chart), the contract between the Chinese data handler and a foreign data recipient (i.e. the solid line (2) in the chart), and between the foreign data recipient and the data subject (i.e. the dotted line (3) in the chart). Because there is often no direct contractual relationship between the data subject and the foreign data recipient who does not directly collect the personal information from the data subject, the chart uses dotted line to represent the legal relationship between them. Article 39 of the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law provides that where personal information handlers provide personal information overseas, they shall notify the data subject of matters such as the identity and contact methods of the overseas recipient, the purposes and methods of the handling, the types of personal information to be handled, and the methods for individuals to exercise the rights provided by this Law, and obtain the individual’s consents to the cross-border transfer of their personal information. However, the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law does not clarify the legal relationship between the data subject and the foreign data recipient. In the author’s view, the standard contract should provide legal remedies to the data subject against the foreign recipient in case of personal information breach caused by the latter. For example, the data subject should be allowed to directly bring legal actions against the foreign data recipient who breaches the contract and mis–handles the personal information of the data subject. The standard contract between the Chinese data handler and the foreign data recipient, which as of yet has not been released, should not impose any obligations on the data subject; instead, it should ensure that the data subject’s information is well protected. Therefore, the data subject is the third-party beneficiary of the contract between the Chinese data handler and the foreign data recipient. The (1), (2), (3) legal relationship forms a contractual ‘triceratops’.

Although the cross-border data transfer is based on the contract between the Chinese data handler and the foreign data recipient, the party autonomy in deciding the choice of law and choice of court clauses will likely be very limited. The contract will likely require parties to apply Chinese law and resolve their disputes exclusively in China.

- Cross-border information transfer and judicial assistance

Article 41 of the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Act provides that where judicial or law enforcement bodies outside China request the provision of personal information stored in China, the information must not be provided without the approval of the competent Chinese state organs; but where treaties or agreements concluded or participated in by China have relevant provisions, those provisions may be implemented.

This provision addresses cross-border information transfer based on foreign judicial assistance requests. It is China’s response to foreign statutes such as the United States (US) Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (‘CLOUD Act’). The CLOUD Act requires US companies to provide stored data for a customer on any server they own and operate when requested by warrant regardless of where the data is stored (§ 2713 of CLOUD Act).

Moreover, foreign governments or parties might invoke judicial assistance or mutual legal assistance treaties concluded by China to access personal information stored in China. The typical example of the multilateral convention for civil proceedings is the Hague Convention of 18 March 1970 on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters (‘HCCH Evidence Convention’).For criminal proceedings, Australia and China have entered into a bilateral mutual legal assistance treaty (‘the Australia-China Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty’) which is given effect in Australian law through the Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (The People’s Republic of China) Regulations 2007. However, the HCCH Evidence Convention and the Australia-China Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty both impose strict requirements that foreign governments or entities should satisfy before China offer judicial assistance. China can refuse to provide access to these data if it considered that access would seriously impair its sovereignty, security, national interest or other essential interest (see Article 4 of the Treaty).

- Personal information transfer to international organizations

Last but not the least, the Proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law does not address the transfer of information to international governmental organisations. Commenters have correctly pointed out that in the legislative process of the GDPR, the EU legislator missed the opportunity to clarify the applicability of the GDPR to international organisations. How to regulate the transfer of personal information from China to international organisations is also missing in the ongoing legislations of personal data protection law and data security law. China is an emerging host of international organisations, especially those related to the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. Also, the immunities and privileges of international organisations may create complicated conflict of laws issues in investment arbitration. For example, if an investment arbitration regarding a dispute related to a project under the Belt and Road initiative is seated in China, whether all the arbitral participants (e.g. arbitrators, parties of both sides, lawyers and witnesses) should comply with the proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law or whether all or some of them can be shielded by the immunities and privileges of the relevant arbitration institutions such as PCA and ICSID. So, clarifying the applicability of the GDPR to international organizations is critically important and Chinese legislators should not leave this issue unaddressed.

Jie (Jeanne) Huang ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor at University of Sydney Law School, specialising in legal issues in digital trade/e-commerce, conflict of laws and Chinese law.

Suggested citation: Jeanne Huang, ‘Regulating cross-border information flow: the proposed Chinese Personal Information Protection Law’ on ILA Reporter (30 March 2021) <https://ilareporter.org.au/2021/05/regulating-cross-border-information-flow-the-proposed-chinese-personal-information-protection-law-jeanne-huang/>