A fundamental question driving the international debate concerning the regulation of Autonomous Weapon Systems (AWS) (AWS definitions here and here) is whether they can be used in compliance with international law. While state legal reviews of new weapons are important tools to ensure the lawful use of AWS, their utility is challenged by limited state practice and the absence of standard review methods and protocols. However, done properly, state legal reviews are a critical mechanism to prevent the use of inherently unlawful AWS, or, where necessary, restricting their use in circumstances where they cannot predictably and reliably comply with international humanitarian law (IHL).

All states are required to undertake legal reviews of new weapons either because of an express obligation under Article 36 of the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, or to give effect to a broader IHL requirement to ensure the lawful use of weapons in armed conflict. While international law does not require a particular review methodology to be used, the rapid changes to technology that enable autonomy—such as Artificial Intelligence and machine learning—raise the question of how states can practically conduct legal reviews of weapons that are enhanced by such technology.

There is a broadly-accepted traditional method for the legal review of weapons described by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) (in their Guide to the Legal Review of New Weapons, Means and Methods of Warfare). An immediate question that arises with AWS is whether the traditional approach to the legal review of weapons is sufficient to determine their legality. In short, the answer is no. In our view, the legal review method of AWS is likely to differ in a number of ways.

First, an AWS legal review will require greater participation in the study and development of a weapon to ensure the reviewing state’s legal obligations are understood and incorporated in the design, programming, training and development of the weapon. Second, the requirement to assess any AWS functionality that engages the reviewing state’s IHL obligations—such as distinguishing between lawful and unlawful targets—will require careful consideration of issues such as the degree of human input to targeting decisions, the acceptable standard of machine compliance, and the measures for ensuring ongoing compliance with IHL. Such assessments are not normally part of a traditional review, as the reviewer will presume the weapon’s human weapon operator will comply with the law. Finally, the use of AI enhanced weapons that are capable of machine learning will require ongoing legal review to assess any self-initiated changes to the weapon’s method of operation. Consequently, the weapon review process may require constant revision throughout the weapon’s lifecycle.

With these differences in mind, we propose six key legal review questions that a state may consider in undertaking the legal review of AWS:

1. When should a legal review of an AWS occur?

For States Parties to Additional Protocol 1, Article 36 requires the legal review during the ‘study, development, acquisition or adoption’ of a new weapon, means or method of warfare. The triggering requirement for review is less clear for states not party to Additional Protocol 1, however, practicality suggests that they should also undertake a review before the weapon is used in armed conflict.

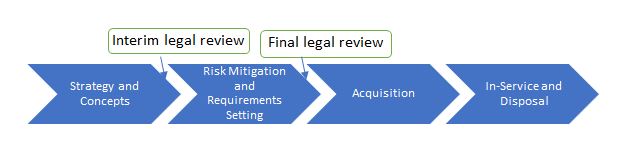

In some cases, a state may undertake a single legal review in the final stages of the weapon acquisition process to satisfy this obligation. This approach is suitable for traditional weapons where the weapon-system itself complies with the underpinning principles of IHL, and it is the operators—who are subject to international law accountability mechanisms—that are responsible for ensuring the means and method of employment of the weapon complies with the law. Consider, for example, that the weapon system complies with broad obligations under the law by not utilising cavitating rounds, chemical rounds, or rounds that when fired would cause indiscriminate effects.

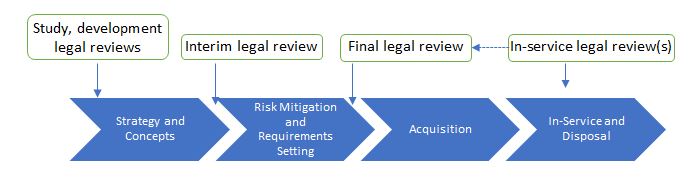

We suggest that this approach is too narrow for AWS, which will require legal review throughout its capability life cycle. The algorithms that drive the autonomous systems must operate in compliance with a state’s legal obligations in mind. Thus, a thorough AWS legal review should be part of the entire design and procurement process, both informing the AWS development and assessing its legality during use. This may require participation in state-sponsored research and development, for example, through organisations such as the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) or Australia’s Defence Trusted Autonomous System Centre for Cooperative Research.

It follows that a legal review of AWS is unlikely to be a singular process and will require a broader, iterative, multidisciplinary and ongoing approach. This may extend throughout the weapon’s life cycle to assess its ability to operate in multiple environments that require the AWS to interpret data which differs from that upon which its performance was initially reviewed. It will also address advances in technology which change the AWS operation.

Small operational changes could be assessed by an operational or field legal review that builds upon the reviews conducted pre-introduction into service. More significant changes—for example, the introduction of machine learning or improvements in the AI’s contextual reasoning capability—may require analysis at the strategic level of Government.

2. Which components of an AWS are legally reviewable?

An AWS, as the name suggests, will likely consist of a number of discrete components operating together as a system. Not all components will, as a matter of law, require review. It is likely that the first AWS will comprise existing conventional weapons whose method of use is augmented by AI or deterministic programming to reduce or enhance human operation. For example, the Australian Defence Force and BAE Systems are testing modified M113 Armoured Personnel Carriers for ‘optionally manned operations’. Near-future AWS will not be fully autonomous, but will instead operate as part of a combatant-AWS team.

For this reason, we argue that the focus of the legal review for such AWS will be those aspects of the weapon’s operating system that enable autonomous operation and engage IHL rules and principles. This analysis may consider and build upon an earlier legal review of the weapon, but extend to whether the autonomous functions will perform lawfully. Other components—such as the mobility platform (air, land or sea), non-harming functionality, and communications system—will only be relevant to the legal review to the extent that they enable or restrict the autonomous operation of the weapon.

3. How will artificial intelligence be assessed by a legal review?

The analysis required to determine the legality of an AWS will be broader than that for a conventional four-part legal review process applied to human controlled weapons. These parts of the traditional weapon review criteria (summarised in Diagram 3) are recognised as: (1) confirming the object is the subject of a legal review and, if so, identifying its normal or expected use; (2) determining compliance with specific treaty and customary international law prohibitions and restrictions; (3) assessing the weapon against general IHL prohibitions (unnecessary suffering/superfluous injury and indiscriminate effects); and (4) applying other considerations of law and policy (including, for example, the Martens clause, which states that, in the absence of specific treaty rules, ‘civilians and combatants remain under the protection and authority of the principles of international law derived from established custom, from the principles of humanity and from the dictates of public conscience.’) Following consideration of these parts, a traditional weapon review would generally conclude subject to any later weapon modifications.

The legal review of an AWS would include these steps, but will require additional analysis to assess the legality of the operating system enabled by AI. This can be achieved by systematically identifying the function of each component that directly or indirectly engages IHL obligations. These are considered in the context of the weapon’s normal and expected use, the data inputs, and its likely operating environments. Ultimately, the review must become an iterative process, often cyclical and evolving, where the legality of the AWS is the subject of ongoing consideration by the reviewing state as the AWS development and use evolves.

Copeland and Reynolds suggest that one approach would consist of progressive testing levels, starting with code review followed by virtual and physical testing to assess the individual IHL tasks in each of the use scenarios at each level of the loop. The progressions would permit the early identification of limitations in the weapon’s IHL decision-making ability. In turn, this would inform further development of the AI for subsequent re-assessment, or the possible imposition of operational limitations on the weapon’s decision making, including programming a requirement for human input to make the relevant decision.

4. Identify which IHL and international law obligations are relevant to the AWS’s normal or expected use

Unlike the legal review of a conventional weapon, a legal review of an AWS will require a legal reviewer to, as far as possible, assess each IHL rule directly or indirectly relevant to the AWS’s normal or expected use in the context of its anticipated operating environment. (For States Parties to Additional Protocol 1, these rules are predominately found in Parts III and IV of the First Additional Protocol.)

To illustrate this difference, the legal review of a conventional, human-controlled heavy machine gun will consist of an analysis of the four-part legal review described above. The review will not consider the IHL rules regulating certain methods of warfare—such as constant care, denying quarter, safeguarding an enemy hors de combat, ensuring respect for and protection of civilians, distinguishing between civilian population and combatants, or precautions in attack—as these are subject to individual and state accountability mechanisms. If, however, the same heavy machine gun was employed as the weapons component of an AWS intended to autonomously perform a self-defence role, these rules would need to be assessed in detail to ensure that individuals deploying the AWS to conduct this function on their behalf, and the state using it, do so consistently with their IHL obligations.

It follows that an essential step in the review process for AWS is to map these obligations against the AWS’s normal or expected use across a range of scenarios, operating environments, and data inputs. One approach is to create a tool that enables each rule to be assessed and recorded across the various environmental conditions and data inputs. For example, the ability to distinguish between a civilian object and a specific military objective could be addressed by a single line in an IHL matrix that records the data necessary for recognition and identification of the target, and other relevant factors such as environmental conditions including light, obscuration, distance between sensor and object, or whether the terrain was open or complex (such as an urban setting).

Such an approach would inform both the study and development by enabling the AI engineers to design, program and train the system to be capable of performing specific roles and the subsequent test and evaluation to record the AWS’s ability to meet the specific performance standards in different contexts. It permits the legal review to identify which AWS tasks are capable of being lawfully performed and in what circumstances. Shortfalls in the AWS performance standards would be recorded and either further researched and developed, or the AWS’s ability to perform that task could be restricted or prohibited.

5. Determine which standard of compliance should apply

The legal review of a weapon involves detailed analysis of weapon performance to determine whether it can meet the reviewing state’s IHL and international law obligations. In many cases, for example, the assessment must determine whether a weapon causes superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering. This process involves both science and art and requires advice from experts from a range of fields.

In other cases, the assessment may be undertaken with more mathematical precision. For example, determining the accuracy and reliability of the AWS’s ability to distinguish between objects or persons will be possible through testing and evaluation. To do this, the reviewing state should determine what standard it will require to assess the AWS’s ability to perform a specific task lawfully. In the case of Galic, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia required a ‘reasonable belief’ to determine whether a person or object is a lawful target. The reviewing state may require, from an ethical perspective and as a matter of policy, an AWS performing a distinction role to achieve a higher standard than reasonable belief, though what is considered ‘reasonable’ in the context of autonomous decision-making systems also requires careful policy and legal consideration by the reviewing state.

6. Decide which AWS functions the legal review will recommend be prohibited or restricted

A legal review of a conventional weapon will generally result in one of three recommendations for the reviewing state to consider: the use in armed conflict is unlawful; the use in armed conflict is lawful but with restrictions on its methods of use; or, the use in armed conflict is lawful.

A legal review is likely to identify variations in an AWS’s ability to perform specific tasks lawfully. For example, an aerial drone-based AWS may be capable of distinguishing a military objective to the required standard from 300 metres, but can only meet the same standard from 30 metres where the object is obscured by smoke or cloud. In this case, the legal review would recommend restrictions on the use of the AWS for this particular task to ensure the required standard of compliance.

Given the autonomous nature of these weapon systems, there must be some kind of control mechanism in place to address these differing methods or means for use of the weapon system, which may require careful engagement in the policy and legal considerations relevant to the use of the subject AWS.

Conclusion

The use of AWS in armed conflict holds the promise to increase accuracy, accountability, and reliability of the use of force, which in turn can increase a state’s compliance with IHL and reduce harm to non-combatants. However, prior to the deployment of such systems, altered approaches to the existing weapons review processes must be considered to ensure the AWS is used in compliance with IHL. These reviews will be different from those utilised for conventional weapons and must be engaged during the design and development stages of the AWS. To properly discharge the obligations of states to utilise AWS lawfully, the Article 36 review of the use of the weapon must be as iterative as the growth and evolution of the weapon’s technology and autonomous systems themselves.

Lauren Sanders has recently completed her doctoral studies in international law, focusing upon enhancing international criminal law accountability and enforcement measures. Lauren is a legal officer in the Australian Army. Damian Copeland is a part-time PhD Candidate at the Australian National University. His research considers the Article 36 legal review of weapons enhanced by Artificial Intelligence. Damian is a legal officer in the Australian Army. This article represents the authors’ personal views and does not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force or Australian Government.